My aunt still teases me about the first time she met me, before she got engaged to my uncle. Apparently, three-year-old me arrived at a family party in Boston, in the depths of winter, in a full-on hissy fit because my mother forgot my patent leather party shoes so I was doomed to wear ugly snowboots for the entire evening.

My aunt still teases me about the first time she met me, before she got engaged to my uncle. Apparently, three-year-old me arrived at a family party in Boston, in the depths of winter, in a full-on hissy fit because my mother forgot my patent leather party shoes so I was doomed to wear ugly snowboots for the entire evening.

Must have been about two years later when I was in kindergarten that my first crush David and I were playing pretend in the nook under the table. He said he wanted to tell me a secret, and he leaned in and awkwardly kissed my ear. I remember how my tiny heart fluttered with happiness.

Somewhere there’s a photo of me, not yet ten years old, in a pink tulle tutu with a pink satin bodice hand-embroidered with silver lace and sequins. My mother made it for me, for my birthday, because I wanted to be a ballerina. The picture shows me trying my best to smile, but you can see the tears on my cheeks. Not from joy, no. I cried inconsolably when I put it on and looked in the mirror because I’d dreamed it would make me LOOK like a ballerina… tall and shapely and womanly, not a little girl anymore with my little-girl tummy sticking out.

By the time I was twelve, I was simultaneously thrilled and terrified to exist in a hail of catcalls. I didn’t know what to do with it, but I craved the attention that I attracted with my newly curvy hips in my favorite Chic stretch jeans and my hair curling-ironed and Aquanetted to great heights. Then at fourteen, I felt vaguely that being sexually harassed at my first job was a badge of becoming a woman, and I wanted womanhood desperately. I’d always wanted it desperately, from these earliest memories.

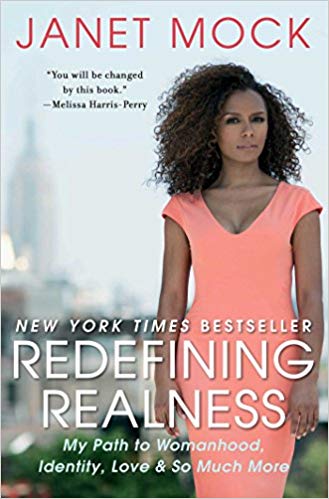

So did Janet Mock. Listening to the audiobook of her memoir, Redefining Realness, I just kept nodding my head as I recognized exactly how she felt growing up, the way she dressed up in her grandma’s clothes as a kid, what it felt like to experience her first stirrings of attraction to boys, how as a teenager she “validated her womanhood by how many men’s heads she turned.”

Her journey, my journey. Except that she was assigned male at birth. And she was poor, and she is of mixed Hawaiian and Black descent: marginalization upon marginalization upon marginalization. So much of what came so easily to me, she won for herself. And more, since she’s the one with a Masters degree, a bestselling book, and a major magazine byline.

I’m so grateful that she shared her powerful story, because it helped me start to understand trans identity and intersectionality more deeply. For example, she uses her own life to illuminate how her family’s history of being colonized (on her Hawaiian side) and enslaved (on her African-American side) resulted in her generation’s precarious poverty, which limited her access to health care and pushed her into sex work. At the same time, she emphasizes how Native traditions of seeing beyond Western gender binaries were a source of strength and community that sustained her.

A few of the moments that stood out most strongly to me from her journey as she shared it:

- Her defense of becoming a sex worker to earn money for her transition, coupled with her searing recognition that she and many other trans women (especially trans women of color) didn’t really have freedom of choice about this: “We make choices as individuals, but we can’t detach ourselves from the societal framework.” Later, she says, “We were groomed by an entire system that failed us.” Such a vivid statement on the interplay of personal responsibility within systems of oppression.

- “I was so busy surviving, I couldn’t think about choices or consequences.” I’ve never heard a clearer encapsulation of the trap of poverty.

- Why she doesn’t feel obligated to tell people she’s trans: “Frankly, people’s assumptions are not my problem.” If they look at her and don’t realize it’s possible she might have been assigned male at birth, it’s not her job to tell them — especially in a society that makes that risky.

Towards the end, she looks back at her life so far and says that her journey has been “from me to more myself.” Hey! That’s my journey too! In all this, I don’t mean at all to appropriate hers… but isn’t that what all of us are trying for? To become more like the person we aspire to be? I just don’t know how I could possibly listen to her memories of growing up feeling like a woman — memories that mirror my own — and how incredibly much she endured to live that truth, and then refuse to accept and respect her as a woman.

I just hope someday I can find half of her strength in myself. And use mine to help change things so that people like Janet Mock don’t need to be so damn strong all the time.